Will the Real Oppressor Please Stand Up?

This essay is written as a personal reflection on humanity's inability to uphold true justice. It is a call for self-examination and ethical courage - in a world where no one can claim full innocence. Not even I.

And it came to pass that the Emperor, considering himself the purest among men, entered the Court of Accountability. His voice sounded like trumpet blasts:

"My people have been wronged! Let me open the treasury, that reparation may be made!"

But he who sternly pointed his finger at the peoples of other lands had forgotten that his own hands, too, were stained with the dust of injustice.

"You all," he cried, "are guilty of slavery and plagues of the ages - pay with generous hand!"

Then an old man stepped forth from the crowd and spoke:

"But where is your purse, O Emperor, and where your robe of righteousness? Were you yourself not also a tool in the chain of injustice?"

And the Emperor reached for his belt - but found neither pouch nor purse. He looked downward and noticed: his body was naked. And true judgment stood before him, as clear as a mirror, from which one cannot escape oneself.

And the people held their tongues, for those who eagerly point at another's guilt must first face their own.

Time for a history lesson - and some reflection.

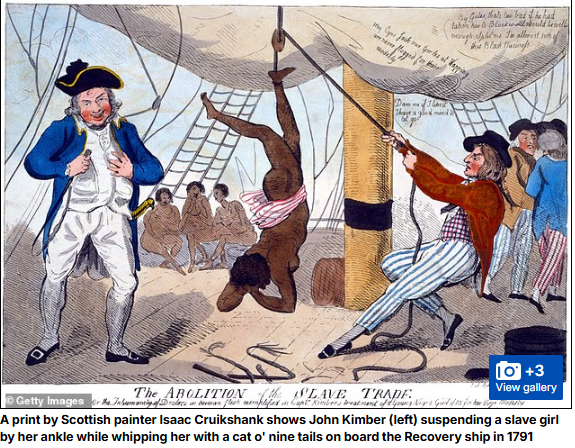

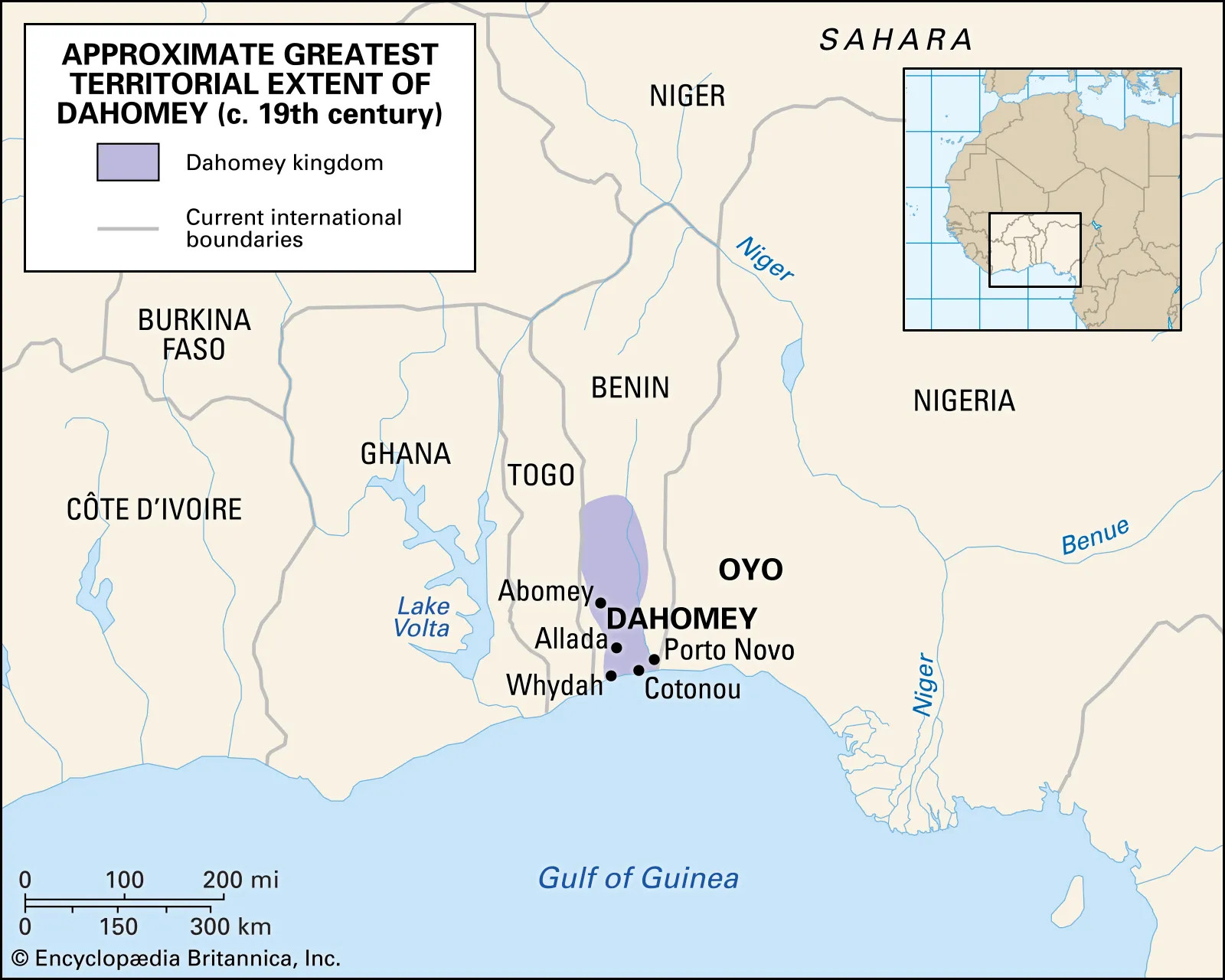

Dahomey: A West African State Built on the Slave Trade

The Kingdom of Dahomey (c. 1600–1904) emerged as a dominant West African state after conquering coastal states such as Allada and Whydah.

With access to the Atlantic coast, Dahomey became a major exporter of enslaved people, relying heavily on warfare and raids — often conducted by its militarized army, including elite female regiments — to capture human beings for trade. Many of these captives were sold overseas, while others remained as forced laborers within the kingdom.

Dahomey also maintained ritual institutions tied to royal and ancestral cults.

In the annual "Customs" ceremonies, war captives, criminals, or prisoners were sometimes sacrificed in human-blood rituals, which served to reinforce the monarch's spiritual and political authority.

Under King Ghezo (1818–1858), the transatlantic slave trade became the central economic pillar.

Despite pressure from the British to abolish slavery, Ghezo defended the trade as "the source and the glory of our wealth." Though Dahomey agreed in 1852 to end slave exports under a treaty, the trade resumed by 1857 — illustrating the kingdom's deep structural reliance on human bondage.

Slavery in America began because some Africans sold other Africans to European masters. And now they're making money from that history again - perhaps simply skilled businesspeople?

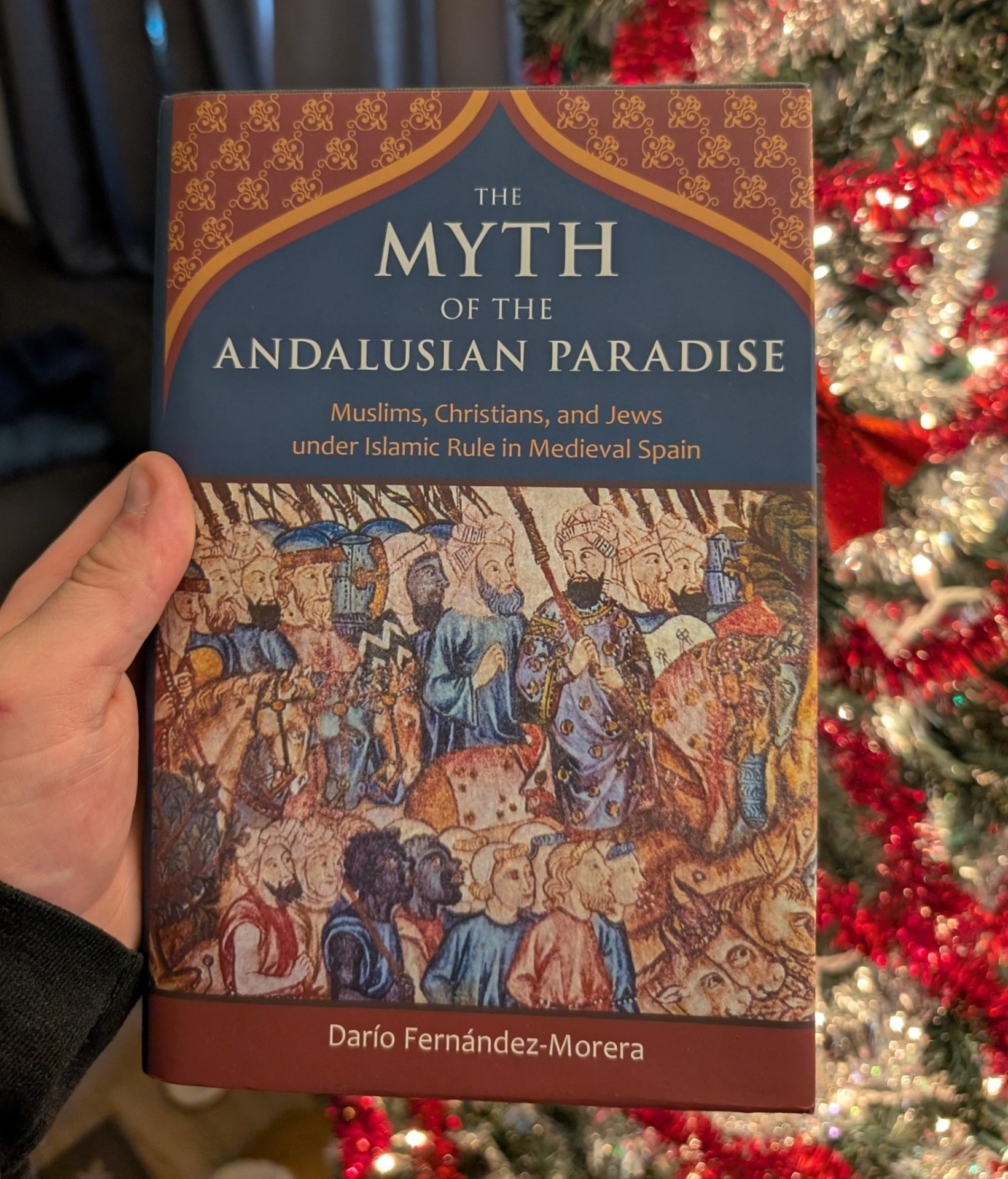

The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise

Since the eighteenth century Enlightenment, the critical construction of a diverse, tolerant, and happy Islamic Spain has been part of an effort to sell a particular cultural agenda, which would have been undermined by the recognition of a multicultural society racked by ethnic, religious, social, and political conflicts that eventually contributed to its demise -- a multicultural society held together only by the ruthless power of autocrats and clerics. This ideological mission would then be the ultimate reason for the tilting of the narrative against Catholic Spain ... In the past few decades, this ideological mission has morphed into "presentism" an academically sponsored effort to narrate the past in terms of the present and thereby reinterpret it to serve contemporary "multicultural," "diversity," and "peace" studies, which necessitate rejecting as retrograde, chauvinistic, or, worse, "conservative" any view of the past that may conflict with the progressive agenda. Thus, it is stupendous to see how some academic specialists turn and twist to downplay religion as the motivating force in Muslim conquests, and even to question the invasion of Spain by Muslim Arab-led Barber's as the conquest of one culture and its religion by another. Failing to take seriously, the religious factor in Islamic conquests is characteristic of a certain type of materialist Western historiography which finds it uncomfortable to accept that war and the willingness to kill and die in it can be the result of

someone's religious faith -- an obstacle to understanding that may reflect the role played by religious faith in the lives of many academic historians. This materialist approach has also generally prevailed in scholarly analyses of the Crusades."

~ Darío Fernández-Morera, The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise, Pg. 4-5

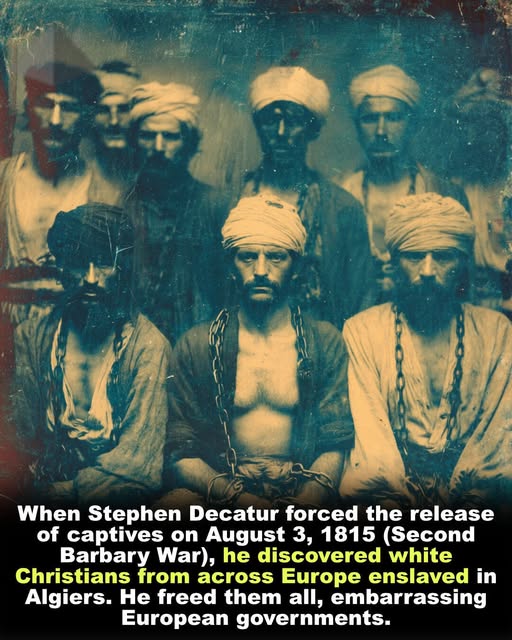

The End of the Barbary Slave Trade: How a Young Nation Defied the Corsairs

In 1815, shortly after the conclusion of the War of 1812, the United States turned its naval might toward the North African coast to confront a crisis that had plagued the Western world for centuries. For generations, the Barbary States had operated a brutal system of state-sponsored piracy, capturing merchant vessels and forcing their crews into a vast network of white slavery.

While modern history often overlooks this chapter, thousands of Europeans and Americans were held in bondage across the Islamic world, where they were either sold into hard labor or held in dungeons for exorbitant ransoms.

Commodore Stephen Decatur led a squadron of ten American warships into the Mediterranean with a clear mandate to end this practice. His campaign was remarkably swift. After capturing the Algerian flagship and killing their top admiral, Decatur sailed directly into Algiers harbor.

Faced with superior firepower, the Dey of Algiers was forced to sign a treaty that abolished all future tribute payments and demanded the immediate release of all captives. This intervention resulted in the liberation of hundreds of white slaves, including sailors and traders from Italy, Spain, Sicily, and Portugal, some of whom had been enslaved for over a decade.

This victory by a young United States shattered the long-standing European policy of appeasement.

For centuries, major powers had simply paid tribute to avoid the enslavement of their citizens, viewing the corsairs as an unavoidable reality of Mediterranean trade.

The American refusal to submit demonstrated that military resolve could dismantle the slave markets of North Africa. This shift in doctrine inspired a coordinated Anglo-Dutch expedition just a year later, which further crippled the corsairs' power. Ultimately, Decatur's mission didn't just protect American commerce; it signaled the beginning of the end for a centuries-old system of Mediterranean slavery, proving that the cycle of ransom and human trafficking could be broken through decisive action.

The Viking Truth No One Talks About

Genetic studies reveal a haunting truth: when Vikings settled Iceland, nearly half the female ancestry was Irish. That's not poetic, it's the legacy of slavery.Let's talk about something that rarely makes it into the Viking fanfare: the women who were taken. When we picture Vikings, we think longships, raids, and rugged warriors. But behind that image is a brutal reality, especially for Ireland. From the late 8th century onward, Norse raiders repeatedly struck Irish coasts, not just for treasure, but for people. And the most "valuable" captives? Women.These women were taken as thralls, the Norse word for slaves. Some were sold, others kept. Many were transported across the sea, eventually ending up in places like Iceland, which was colonized by Norse settlers in the late 9th century. But here's the twist: modern DNA studies show that while Iceland's male ancestry is overwhelmingly Norse, the female ancestry is about 50% Gaelic, mostly Irish and Scottish.That means the women who helped build Iceland's population weren't Norse wives, they were captives. Enslaved. Displaced. And yet, they became mothers, workers, cultural carriers. Their mitochondrial DNA, passed from mother to child, still echoes through Iceland's population today.It's a sobering reminder that colonization isn't just about conquest. It's about who gets taken, who gets silenced, and who gets woven into the story without ever being named.

The Arab slave trade lasted about 1200 years that's about 3 times as long as the transatlantic slave trade lasted and yet we never hear about the Arab slave trade. Why is that?

One of the main reasons is because many of those slaves were castrated or killed so that's why we don't see a large African disapora population in Arab nations today. (source: Bernard Lewis, Race and Slavery in the Middle East; Paul Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery)

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, slave auctions in parts of the United States and the Caribbean were sometimes closed on Jewish holidays. In cities like Charleston, Richmond, and Newport, many traders were of Jewish descent, so auctions there were often not scheduled on the Sabbath or major holidays. This was a practical choice by the traders themselves rather than a general law for the entire market.

Slavery has existed for centuries across many civilizations, but Islamic societies practiced it the longest, affecting both Black and White people, and it still continues today in places like Mauritania. Groups such as the Yazidis are also still being enslaved.

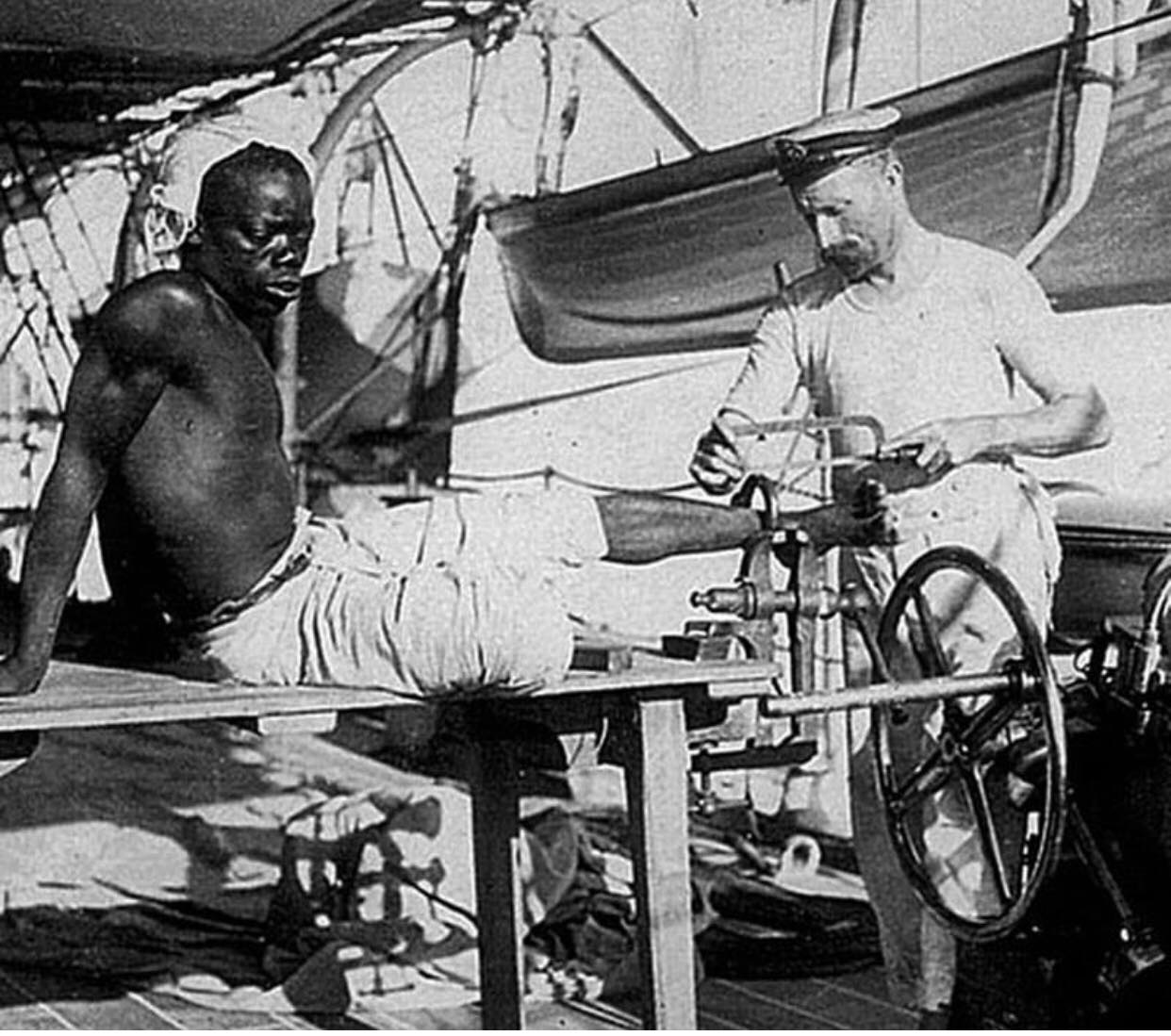

Slave shackle being removed by a British sailor, 1907. The son of the man who took the photograph wrote the following account of what happened:

"The pictures were taken by my father who was serving aboard HMS Sphinx while on armed patrol off the Zanzibar and Mozambique coast in about 1907. They caught quite a few slaver traders, and those particular slaves that are in the pictures were liberated while he was on watch. That night a dhow (sailing vessel) sailed by and the slaves were all chained together.

He raised the alarm and they got them onto the ship and got the chains knocked off them. They then questioned them and sent a party of marines ashore to try to track the slave traders down.

They caught two of them and I believe they were of Arabic origin. My father thought the slave trade was a despicable thing that was going on, the slaves were treated very badly so when they got the slaver traders they didn't give them a very nice time".

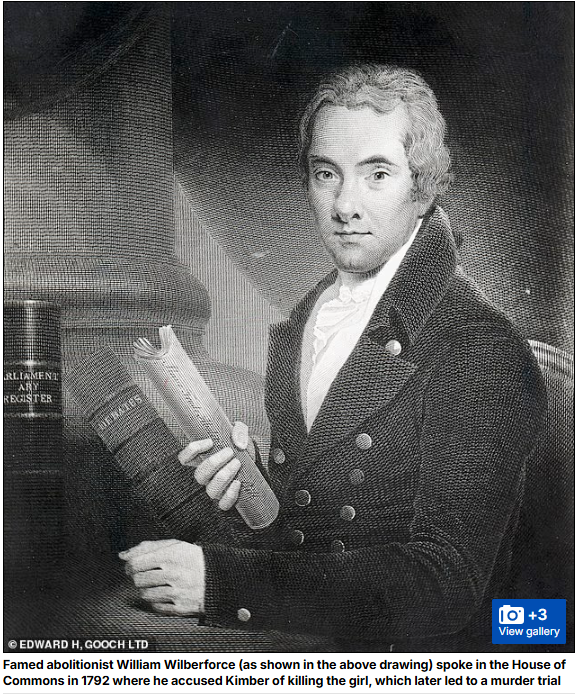

'Yes, these things happened, and yes, they were vile. But they did not happen in some misty, universally shared moral fog. They were the sordid pastime of rich and aristocratic families who treated human beings as inventory, while ordinary people, themselves barely above serfdom, were in no position to profit from or protest against it. What finally cracked the edifice was not polite hand-wringing but relentless abolitionist propaganda that deliberately dragged the worst of it into the light. "Am I not a man and a brother?" was not subtle. It was not meant to be. It was a moral battering ram, and it worked. Thanks to that pressure, and that outrage, the trade was ended, at least in British-controlled waters. A rare historical moment where organised conscience beat organised greed. Grim beyond words, but proof that shame, loudly applied, can still force change'. - SandraFelchem

Slavery was standard practice throughout human history until it was ended by Christians.

Sadistic human experiments inside Japan's notorious WW2 Unit 731 where PoWs were infected with plague, raped and buried alive are brought to life in ultra-violent Chinese movie, read more

African butcher behind 'some of the most brutal crimes in human history': How warlord Charles Taylor oversaw 250,000 murders with children forced to kill their own parents... but now rots in a British prison, read more

In the 1890s, the Congo state (controlled by Belgian settlers) allowed the companies to maneuver almost entirely freely, which resulted in various atrocities, including the amputation of hands as punishment for those who refused to collect rubber, read more

In 1862, the United States carried out the largest mass execution in its history, hanging 38 Dakota men in Mankato, Minnesota. The trials were rushed, unfair, and conducted in a language many did not understand—after years of broken treaties, stolen land, and deliberate starvation. read more

Humans can be very cruel. We should acknowledge those who have left their cruel practices behind, and work on educating and reforming those who still commit heinous acts.

Empire/Power

Regions

Period

Led by

Victims ±

Remarks

British Empire

Worldwide

16th–20th century

Elizabeth I, Victoria

10–35 million

Transatlantic slavery, colonial wars, famines

Mongol Empire

Asia, Eastern Europe

13th–14th century

Genghis Khan

20–60 million

Slavery, mass destruction, deportations

Ottoman Empire

Middle East, Balkans, North Africa

1299–1922

Osman I, Suleiman the Magnificent

1–5 million

Slavery via Balkans & Africa, jihad, sharia

Islamic Caliphates

Middle East, North Africa, Spain

7th–13th century

Abu Bakr, Umar Ibn al-Khattab

1–5 million

Slavery sanctioned under Islamic law

Roman Empire

Europe, North Africa, Middle East

27 BC–476 AD

Augustus, Trajan

1–5 million

Slavery as foundation of economy

Spanish Empire

Americas, Philippines, Europe

15th–19th century

Charles V, Philip II

10–20 million

Slavery, indigenous mortality

Portuguese Empire

Brazil, Africa, Asia

15th–20th century

Henry the Navigator

1–5 million

Early transatlantic slave trade

French Empires

Africa, Asia, Americas

17th–20th century

Napoleon Bonaparte, Louis XIV

1–5 million

Slavery in colonies

Dutch Empire

Indonesia, Suriname, Caribbean

17th–20th century

Jan Pieterszoon Coen

1–4 million

VOC/WIC slavery and plantations

Russian Empire / USSR

Eurasia

16th–20th century

Peter the Great, Stalin

20–40 million

Slavery, serfdom, Gulags

Persian Empires

Iran, Mesopotamia, Egypt

From 6th century BC

Cyrus the Great, Darius

1–2 million

Slavery (relatively mild)

Chinese Empires

East Asia

2000+ years

Qin Shi Huang, Kublai Khan

10–30 million

Slavery, serfdom, forced labor

Macedonian Empire

Greece to India

4th century BC

Alexander the Great

1–2 million

Slavery as war loot

East Asia, Pacific

19th–20th century

Emperor Hirohito

6–20 million

Slavery, forced labor, comfort women

Incas

Andes

13th–16th century

Pachacuti–Atahualpa

1–2 million

Slavery, Mita system (forced labor)

Aztecs

Central Mexico

14th–16th century

Moctezuma II

1–2 million

Slavery and human sacrifice

Assyrians

Mesopotamia

2000–600 BC

0.5–1 million

Babylonians

Southern Mesopotamia

1800–500 BC

Hammurabi, Nebuchadnezzar

Unknown

Slavery codified in law

Hittites

Anatolia (Turkey)

1600–1200 BC

Suppiluliuma I

Unknown

Enslaved war captives

Zulus

Southern Africa

19th century

Shaka Zulu

1–2 million

Slavery, Mfecane (ethnic cleansing), domination of rivals

Songhai

West Africa

15th–16th century

Sonni Ali, Askia Muhammad

Unknown

Slavery as trade commodity

Ayyubids

Egypt, Syria, Palestine

12th century

Saladin (Salah-ad-Din)

Unknown

Slavery permitted, regulated

Belgian Empire

Congo (Congo Free State)

1885–1908 (private rule)

Leopold II

10–15 million

Slavery, forced labor, amputations, rubber terror

German Empire

Germany, Africa, Oceania

1871–1918

Wilhelm I & II, Bismarck

1–2 million

Slavery, Herero genocide, forced labor

Third Reich Germany

Europe, North Africa (temporarily)

1933–1945

Adolf Hitler

40–70 million

Mass slavery, Holocaust, labor camps

United States

North America, Pacific, Caribbean, Latin America, Middle East

18th–21st century

George Washington to George W. Bush

10–30 million

Slavery until 1865, westward expansion (Manifest Destiny), wars (Mexico, the Philippines, Iraq), economic and military hegemony, annexations of Hawaii, the Philippines, Guam, Puerto Rico, and Texas (1845) — followed by the incorporation of California, Arizona, New Mexico, and more. (That is the historical weight behind the Mexican saying: 'We didn't cross the border — the border crossed us.')"

Serbian Empire

Balkans (Kosovo, Macedonia, Albania)

12th–14th century

Stefan Dušan

Unknown

Slavery, serfdom

Akkadian Empire

Mesopotamia

ca. 2334–2154 BC

Sargon of Akkad

Unknown

Slavery, first known empire

Egyptian Empire

Egypt, Nubia, Levant

ca. 2686–1070 BC

Ramses II, Thutmose II

Unknown

Slavery, monumental construction using forced labor

Byzantine Empire

Eastern Roman Empire

330–1453

Justinian I, Heraclius

1–2 million

Slavery, "Christian" empire, heir to Rome

Mughal Empire

India, Pakistan, Bangladesh

1526–1857

Babur, Akbar the Great

1–5 million

Slavery, Islamic empire with cultural flourish

Timurid Empire

Central Asia, Persia, India

14th–15th century

Tamerlane (Timur)

7–17 million

Slavery, violent conquests

Sassanid Empire

Iran, Mesopotamia

224–651

Shapur I, Khosrow I

Slavery, last major pre-Islamic Persian empire

Khmer Empire

Cambodia, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam

802–1431

Jayavarman II

Unknown

Slavery, forced labor

Tibetan Empire

Tibet, Central Asia

7th–9th century

Songtsen Gampo

Slavery, religious empire with brief expansion

Habsburg Empire

Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, Spain, Netherlands, Italy, Balkans

1526–1918 (peak)

Charles V, Maria Theresa, Franz Joseph I

1–2 million

Colonial slavery, oppression, serfdom, Catholic absolutism

Vikings / Norse Kingdoms

Northern Europe, England, Iceland, Russia

Ragnar Lodbrok, Harald Bluetooth

Unknown

Large-scale slavery, pillaging, deportations

Italian Colonial Empire

Libya, Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia

1882–1943

Mussolini, Victor Emmanuel III

Slavery, forced labor, gas attacks, concentration camps

And the list goes on…

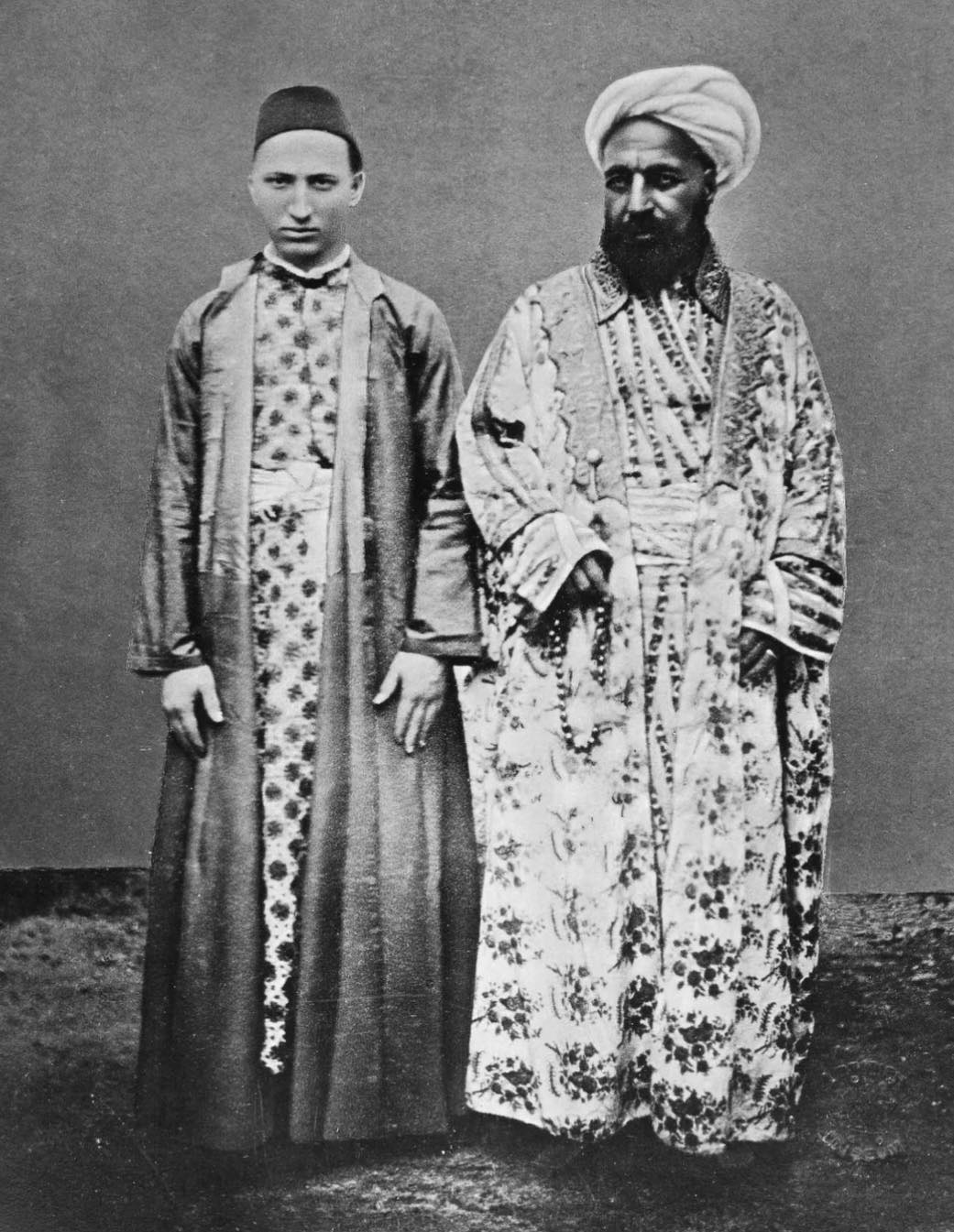

A Meccan merchant and his Circassian enslaved man. Picture taken in Mecca between 1887 and 1888.

This photograph offers a rare visual record of 19th-century Mecca, a period when slavery persisted throughout much of the Arabian Peninsula despite growing international abolition movements.

The image shows a Meccan merchant standing beside a young Circassian boy, identified as enslaved, whose pale complexion reflects the trade in captives brought from the Caucasus region to serve in domestic roles. Their attire—ornate robes and detailed embroidery—reveals both social hierarchy and cultural richness, but beneath that lies the stark reminder of human bondage. For historians, such images illuminate the global reach of slavery beyond the transatlantic context, revealing how systems of servitude connected Africa, Europe, and the Middle East for centuries.

Added Fact: The Ottoman Empire officially abolished slavery in 1889, only a year after this photograph was taken, but the practice lingered informally in many regions of the Arabian Peninsula well into the 20th century (source)

Note: Mesopotamia (modern-day: Iraq, parts of Syria, Iran, Turkey, Kuwait)

-

Iraq — the core of ancient Mesopotamia (Babylon, Ur, Nineveh)

-

Syria (northeast) — border region influenced by Assyrians and Akkadians

-

Iran (southwest) — especially Khuzestan region (Elamites, Mesopotamian influence)

-

Turkey (southeast) — source of Tigris and Euphrates

-

Kuwait — southern edge of ancient Sumer

Other historical regions:

-

Ottoman Empire: Turkey, Greece, Syria, Iraq, Egypt, Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Balkans, Libya, Algeria, Tunisia

-

Roman Empire: Italy, France, Spain, Portugal, Germany, Britain, Greece, Turkey, North Africa, Middle East

-

Aztecs: Mexico

-

Khmer Empire: Cambodia, parts of Thailand, Laos, Vietnam

-

Songhai: Mali, Niger, Nigeria

-

Zulus: South Africa

-

Babylonians, Hittites, Akkadians: Iraq, Turkey, Syria

-

Byzantine Empire: Turkey, Greece, Balkans

-

Mughal Empire: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh

-

Macedonian Empire: Greece, Egypt, Iran, Afghanistan, India

-

Vikings / Norse: Scandinavia, Iceland, England, Ireland, Russia

So - how far have we really come after all these centuries? So-called "civilization" is more fragile than we like to admit. As recently as 1977 - while Star Wars was playing in cinemas and computers were entering homes - someone was publicly beheaded by guillotine in France, a democratic Western European country. Not in some medieval dungeon, but in a modern prison, by official state order. We still live on a planet where in parts of Africa, albino children are mutilated or killed because so-called "witch doctors" believe their body parts possess magical powers. In Afghanistan, religious zealots behead mannequins in shop windows - because even a doll's face is seen as sinful. In countries like Indonesia, tons of plastic are dumped into rivers and oceans as if water were a magical landfill without consequences. And world leaders still host climate summits while flying in with private jets - as if aviation isn't part of the problem.

Slavery still exists - in the form of forced labor, child labor, human trafficking, sexual exploitation, and modern debt bondage. It wears a different mask, speaks another tongue, but its essence is unchanged: dehumanization of others for personal gain.

Today, people are no longer shipped across oceans in chains - but are confined in factories, brothels, plantations, and households - often hidden in plain sight. Our clothes, electronics, and food sometimes bear the stains of invisible slavery.

Civilization? It doesn't exist.

Not as long as we are unwilling to sacrifice for it - but quick to pass the cost on to the child sewing our garments, the laborer picking our cheap fruit and the animal suffering for a full fridge or fast snack.

True civilization doesn't ask for comfort, but for conscience.

Not for beautiful words, but for brave choices.

We refuse to trade ease for discipline, hate for compassion, profit for justice, speed for care.

We want the fruits of civilization — without watering its roots.

We praise freedom - as long as it's our own.

We abhor injustice - as long as we don't have to give up comfort for it.

The Boy Who Scared an Industry: The Tragic Victory of Iqbal Masih

Iqbal's story shows that 'slavery' is not just something from history books of hundreds of years ago, but a monster we are still facing today. It reminds us that behind many of the cheap products we use in the West, there is often a hidden human tragedy.

The story of Iqbal Masih is one of the most heart-wrenching examples of modern injustice, but also of incredible human courage. Born in 1983 in Muridke, Pakistan, Iqbal belonged to a poor Christian family. In a country where the Christian minority often occupies the lowest social rungs, his family lived in a cycle of poverty that felt impossible to escape.

The tragedy began when Iqbal was only four years old. His father, Saif Masih, made a desperate and devastating decision. Needing money for the wedding of his eldest son, he took a loan of about twelve dollars from a local carpet factory owner. In exchange for this tiny sum, he handed over his four-year-old son as collateral. While the Bible teaches that a father must provide for his household, the crushing weight of systemic poverty led to a choice that would haunt the family forever.

For the next six years, Iqbal's life was a nightmare. He was forced to work fourteen hours a day, six days a week, tying thousands of tiny knots in expensive carpets. His mother, Inayat Bibi, was powerless to stop it. In their society, women had almost no say in financial matters, and she spent her days working as a domestic servant just to put a bit of food on the table for her other children. Iqbal was often chained to his loom, beaten for mistakes, and fed barely enough to stay alive. This extreme abuse stunted his growth so severely that at age twelve, he still had the body of a much younger child.

In 1992, everything changed. Iqbal learned that the Pakistani government had actually declared bonded labor illegal. At age ten, he escaped his captors and joined the Bonded Labour Liberation Front. Despite being a small boy who had lived his life in chains, he became a powerful orator. He traveled the world, telling audiences that "children should have pens in their hands, not tools." His activism was so effective that it cost the Pakistani carpet industry tens of millions of dollars in canceled orders.

However, standing up to a billion-dollar industry as a twelve-year-old boy is incredibly dangerous. On Easter Sunday in 1995, while visiting his mother and relatives, Iqbal was shot dead while riding his bicycle.

The official police report claimed it was a random accident involving a local farmer, but almost no one believed this. The investigation was full of holes, witnesses were pressured to change their stories, and the man arrested was eventually acquitted.

To this day, the "Carpet Mafia" is widely believed to be behind his assassination. No one was ever truly punished for the murder of this child. The ultimate injustice is that he was sold for the price of a cheap meal, enslaved for most of his short life, and killed just as he was beginning to taste freedom. Although Iqbal is gone, his legacy forced the world to look at the blood and sweat hidden in the fibers of handmade rugs, leading to new laws and protections that save children to this day.Here is the additional section regarding modern-day child slavery to complete your article. It focuses on current facts and specific industries where this injustice still occurs.

The Unfinished Battle: Child Slavery in the Modern World

While Iqbal Masih's courage brought global attention to bonded labor, it is a painful reality that child slavery did not die with him in 1995. Today, millions of children remain trapped in the same cycles of debt and exploitation that stole Iqbal's childhood. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), there are still an estimated 160 million children in child labor worldwide, with nearly half of them performing hazardous work that directly endangers their health and safety.

Modern-Day Examples of Exploitation

The "Carpet Mafia" that Iqbal fought still exists in various forms across different industries:

Cobalt Mining in the Congo: Many of the batteries used in our smartphones and electric cars are powered by cobalt. Thousands of children in the Democratic Republic of Congo work in "artisanal" mines, digging in deep, narrow tunnels without safety equipment for just a few cents a day.

Cocoa Plantations in West Africa: A significant portion of the world's chocolate begins with child labor in countries like Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana. Children are often trafficked from neighboring countries and forced to use machetes to harvest cocoa pods, often under the threat of violence.

The Fashion Industry: In the "fast fashion" supply chain, children are still found in spinning mills and garment factories in South Asia and Southeast Asia. They perform delicate tasks like embroidery or beadwork, much like Iqbal did with carpets, because their small hands are seen as "ideal" for the work.

Brick Kilns in Pakistan and India: Entire families, including toddlers, are still found working in brick kilns to pay off generational debts. They live on-site in extreme heat, molding bricks by hand to pay back loans that—due to high interest—never seem to disappear.

Why Does This Still Happen?

Child slavery continues because it is profitable for those at the top and because of a lack of transparency in global trade. Much like the $12 loan that enslaved Iqbal, poverty is used as a weapon. When parents have no access to healthcare or fair wages, they are forced into "debt bondage," where the child becomes the ultimate price.

Iqbal Masih once said, "Children should have pens in their hands, not tools." As we look at our phones, wear our clothes, or eat chocolate, his words remain a call to action. The injustice he faced is not a thing of the past; it is a hidden part of our modern economy that requires our constant vigilance and voice.

Time for a course correction

Empires have come and gone - by swords, slavery, and crusades. But there was one voice that led no army, annexed no land, and built no empire - yet touched billions of hearts.

Jesus of Nazareth, the only man without sin, left a world-changing legacy without ever drawing a sword or invading a nation. His message traveled further than the borders of any empire - because it rested not on violence, but on love, mercy, and nonviolence.

Rulers throughout history have misused his name to justify wars, establish colonies, or oppress others - completely contrary to his teachings.

Christ called for repentance, not occupation.

Regions

Period

Led by

Victims

Remarks

Kingdom of God

Judea/Galilee (Roman province), global (influence)

1st century AD

Jesus of Nazareth

None (himself a victim of state violence)

No slavery, preached love for the other. No conquests — yet reached billions through compassion, forgiveness, and inner transformation.